In October, my second book, A Rolling Stone: Taking the Road Less Travelled, was released.

How Sport and Black Lives Matter Together

He died in Tucson, Arizona on 31 March 1980 with his wife and other family members at his bedside.

Many of us might wish for a similar image as we move from life to death. There is an unpretentiousness to it, a normality almost. It was lung cancer and he was 66 years old. In Arizona in 1980, the average life expectancy was 74. The USA in the 1980s was the death rate peak for lung cancer for men. It was, by most barometers, an unexceptional death.

Yet that image of supposed normality was far removed from the life that was lived, one far from ordinary.

William Oscar Johnson wrote in Sports Illustrated, he was, “A kind of all-round super combination of 19th-century spellbinder and 20th-century plastic PR man, full-time banquet guest, eternal glad-hander and evangelistic small-talker.” It was reported this man was earning as much as €100,000 per year (over half a million dollars today) for giving two to three speeches per week.

It wasn’t always that way. In the decades before his speech-making career, this man was making $100/month job as a lift operator as well as a part-time petrol station attendant, playground janitor and manager of a dry cleaning firm.

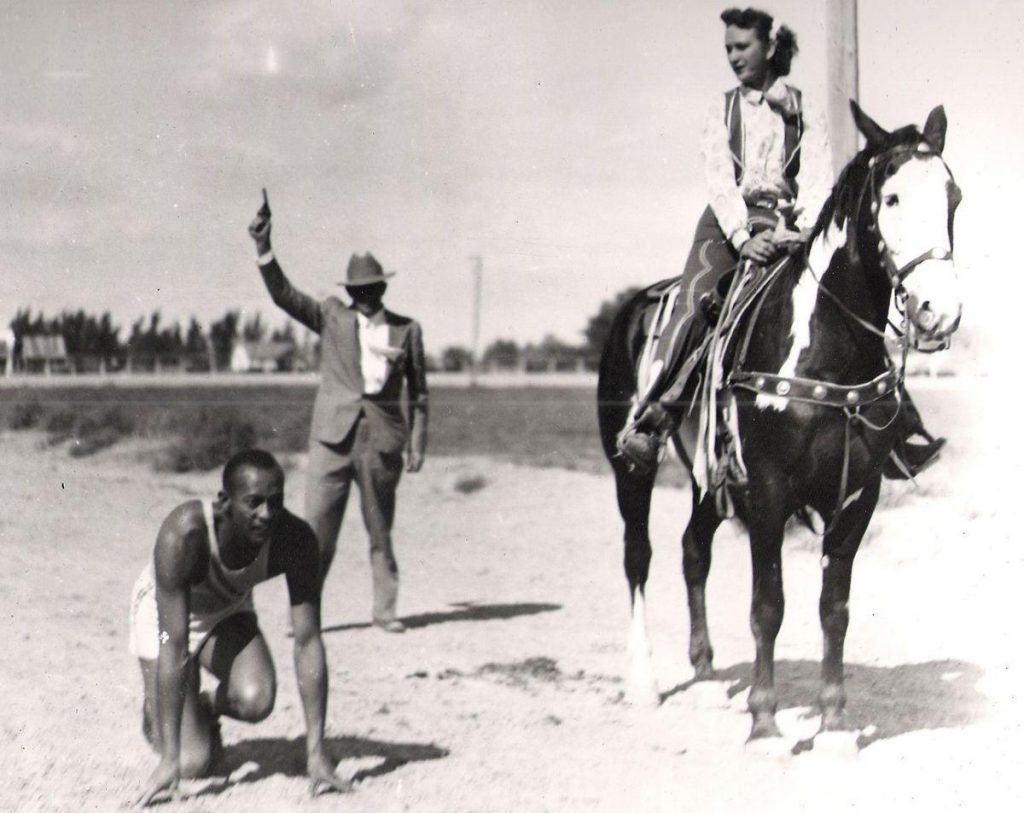

The abilities he possessed that had, and would, bring about global recognition had passed their peak but he reverted to what he knew: running. He competed against small-time sprinters at local meets, giving them a head start and still beating them comfortably. He raced against cars, motorbikes, trucks and finally, animals. Stadiums were full in Alabama and bookmakers were aplenty to watch this runner race against a horse. Even then, his competitive spirit remained intact. He said of his approach, “The secret is, first, get a thoroughbred horse because they are the most nervous animals on earth. Then get the biggest gun you can find and make sure the starter fires that big gun right by the nervous thoroughbred’s ear.” He also said, “Sure it bothered me, but at least it was an honest living. I had to eat.”

Rewind the clock a little further though to 1936. He was recently married to his childhood sweetheart, Ruth, with whom he would share the remainder of his life, and was on a plane bound for Europe. 1930s Europe was in a period of unprecedented change as Hitler and the Nazi Party were set on forming a fascist regime committed to repudiating the Treaty of Versailles, persecuting and removing Jews and other minorities from German society and expanding Germany’s territory.

The Nazi party rose to power in 1933, two years after Berlin was awarded the Olympic Games. Fearing a mass boycott, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) pressured the German government and received assurances that qualified Jewish athletes would be part of the German team and that the Games would not be used to promote Nazi ideology. Hitler’s government, however, routinely failed to deliver on such promises. Regardless, 49 countries attended the Games in Berlin in 1936 which Hitler viewed as the opportunity to spread messages of Aryan race superiority and display Nazi banners and symbols across the newly built sporting stadia.

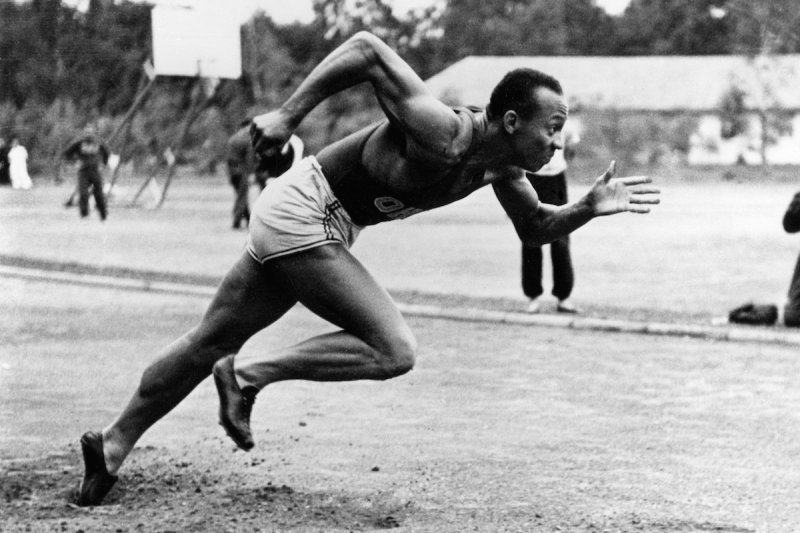

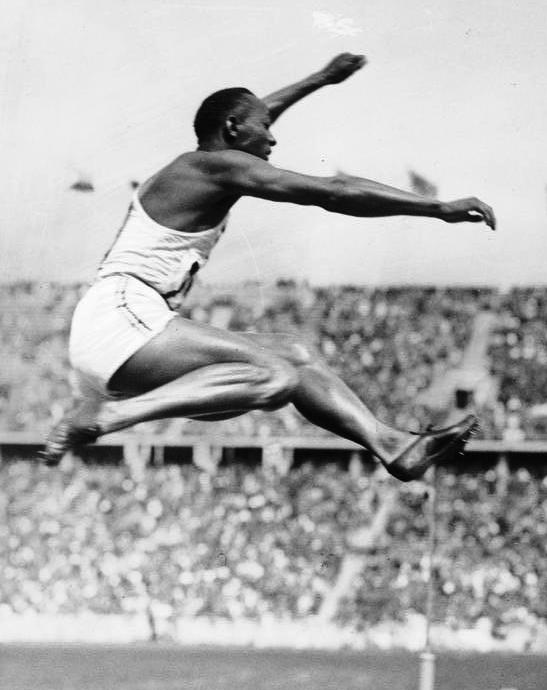

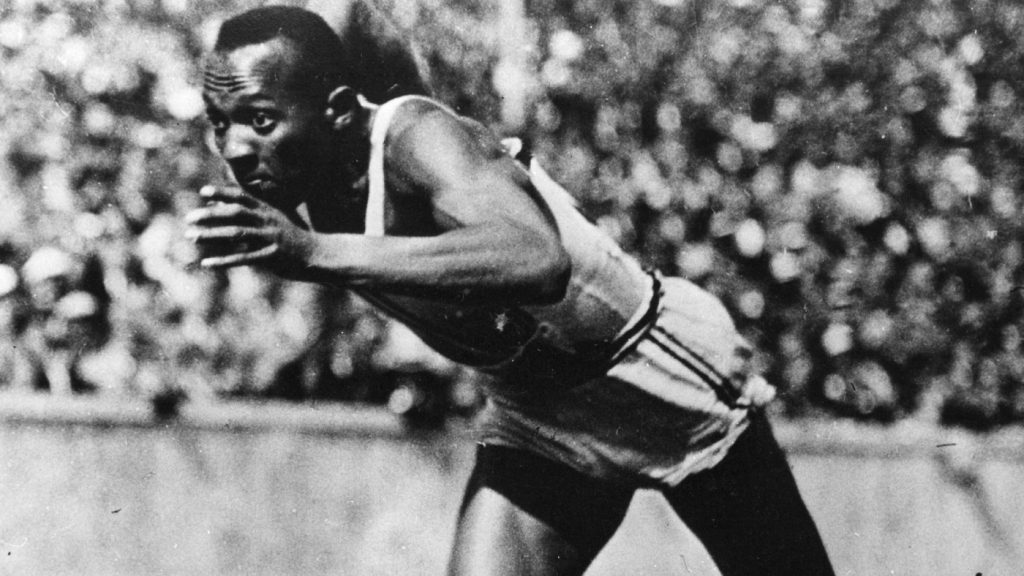

Germany won the games with 89 medals followed by the USA with 56. But history tells us the important narrative was not about who topped the medal table. In a time of 39.8 seconds, the 4x 100-metre relay was won by an American. In a time of 10.3 seconds, the 100 metres was won by an American. In a time of 20.7 seconds, the 200 metres was won by an American. At a height of 8.06 metres, the long jump was won by an American. Four events and one recurring image. One man had managed to win four gold medals, break three Olympic records and one world record.

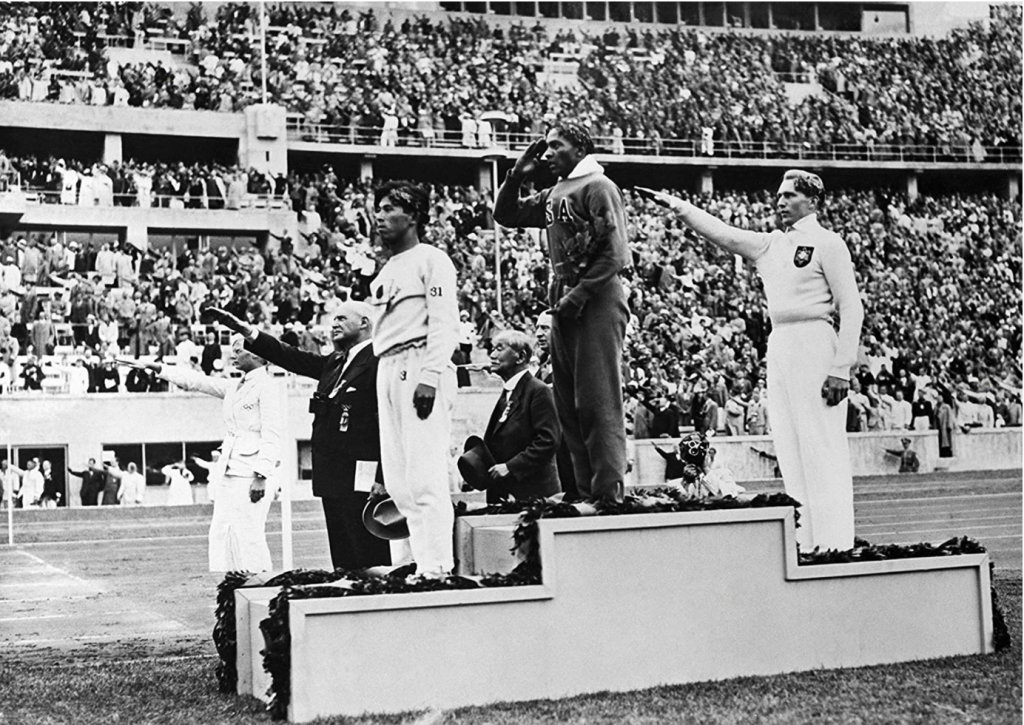

The enduring image from the 1936 Olympic Games was not the medal table but rather the medal ceremony for the men’s long jump. In the background is a stadium full of people directing their gaze forward and left. They are all holding their right arms up and out. Their wrists are straight and their palms are facing downwards. On the ground next to the podium are three officials performing the same gesture. In third place is Naoto Tajima from Japan who has his hands by his side. In the silver medal position on the podium is Lutz Long, a German, in an all-white tracksuit holding the same familiar gesture as the officials and the rest of the stadium. Atop the podium stands the only black person in the photo: an American. He is saluting the flag of the stars and stripes.

He returned to the USA. He did not meet Hitler after his victories but, as he regularly pointed out in the years to come, he did not meet the President either, nor did he even receive a telegram. In his words, “It became increasingly apparent that everyone was going to slap me on the back, want to shake my hand or have me up to their suite. But no one was going to offer me a job.” It was in the years after the 1936 Olympics, the pinnacle of an athletic career where he won four gold medals that the same man became a janitor, a lift operator and raced against horses to pay his rent. He later earned much more money as a public speaker and died in Tucson, Arizona, with his wife, Ruth, and other family members at his bedside.

After his death, President Carter said, “Perhaps no athlete better symbolized the human struggle against tyranny, poverty and racial bigotry.” That man was, of course, Jesse Owens.

32 years after Jesse Owens won those four gold medals in Nazi-ruled Germany in Berlin, the 1968 Summer Olympics were taking place in Mexico City. The winners of the games were the USA with 107 medals. In second place was the Soviet Union with 91. In fifth place was East Germany, West Germany came in eighth.

George Foreman won a gold medal in heavyweight boxing. Swedish pentathlete Hans-Gunnar Liljenwall became the first athlete to be disqualified at the Olympics for drug use – he reportedly had two beers to calm his nerves before the pistol shooting event. John Stephen Akhwari of Tanzania became internationally famous after finishing the marathon, in last place, despite a dislocated knee. Jim Hines, an American, won 100-metre gold with a world-record time and became the first person to break the ten-second barrier for the distance. Hines then went onto break another world record in the 4x 100-metre relay.

In the USA at the time, race riots were taking place and there was a threat of a boycott by the black athletes of the American team. They were disturbed by the controversial idea of admitting apartheid South Africa to the Games and revelations linking the head of the IOC, Avery Brundage, to the racist and anti-Semitic Montecito Country Club he owned in Santa Barbara, California. Hines and the rest of Team USA were, however, persuaded to compete. As with 1936, the enduring image from the games was not the final medal table.

On 17 October 1968, a 24-year-old Texan, the seventh of twelve children, who suffered from pneumonia as a child, was preparing for the start of the 200-metre final. He bends down before kicking out his right leg like a horse raring to go and then drops down to his knees. He places his hands behind the white line and looks ahead.

‘SET!’ His knees rise off the floor. His body is a coiled spring now, leaning ahead, waiting to be released.

BANG! The starting pistol goes off! Ahead of him is another American athlete, a 23-year-old rival born in New York City to Cuban parents. Both Americans power round the bend of the track and enter the final straight together. The athlete in lane four, the New Yorker, is a stride ahead as they enter the final 50 metres. But then the 6ft 3in Texan in lane three propels forward. His rival glances to his left but the now turbo-charged runner surges ahead: high knees, powerful arm drive, graceful movement. The gap is greater by each seemingly effortless stride. With 10 metres to go, he raises his arms aloft celebrating his inevitable victory. The New Yorker glances right. Charging through is an Australian, Peter Norman; his dark hair bouncing with every stride, eyes with laser-like focus, not just on the finishing line but powering through it. The New Yorker stumbles and crosses the line in third place. The first thing he does is to catch up with the Texan, place an arm around his neck, say a few words and extend his right hand to shake that of the winner. The winning time of 19.83 seconds was a world record.

The three athletes are then sat in ‘The Dungeon’ – the room deep within the Olympic Stadium – before their medal ceremony and concoct a plan before walking out to the podium. Lord Burghley, winner of the 400 metre hurdles 40 years before, placed their medals around their necks. As the national anthem played, rather than hold their hands over their hearts and face the American flag, they bowed their heads and raised black-gloved fists. The Texan with his right, the New Yorker with his left. Both men had removed their shoes and wore black socks to symbolise the poverty of the black American community. The Texan wore a black scarf around his neck to represent black pride. All three men, including the white second-placed Australian, wore the badge of the Olympic Project for Human Rights. The Australian was given the badge by the OPHR activist, and member of the US rowing team, Paul Hoffman, on his walk to the podium.

After the medal ceremony, the IOC President, Avery Brundage, became involved after the incident. He deemed it to be a domestic political statement unfit for the apolitical, international forum the Olympic Games were intended to be. He ordered their suspension from the US team and banned them from the Olympic Village. When the US Olympic Committee refused, Brundage threatened to ban the entire US track team. This threat led to the expulsion of the two athletes from the Games.

Back in the USA, the response was lukewarm at best. “A public display of petulance that sparked one of the most unpleasant controversies in Olympic history” according to Time. “A bizarre demonstration” according to Associated Press. The Texan’s contract was cancelled by his agent and he was sacked from his job washing cars leaving him unemployed and broke. The New Yorker soon had no money and had to beg, borrow and steal to pay his rent. Both of their marriages ended within a few years of their medal-winning performance in Mexico.On 17 October 2005, a 20-foot statue was unveiled at San Jose State University to honour two of their former students. The statue is two men standing on an Olympic podium in first and third place. One, the Texan, has his right fist in the air, the other, the New Yorker, has his left. Their heads are bowed. The inscription reads: “Tommie Smith and John Carlos stood for justice, dignity, equality and peace. Hereby the university and associated students commemorate their legacy.”

If we fast-forward again almost 50 years from 1968, a new incident emerges.

It is a long-standing tradition in the USA to play the national anthem before National Football League (NFL) matches. The ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ officially became the national anthem in 1931, and by the end of World War II, NFL commissioner, Elmer Layden, said, “The playing of the national anthem should be as much a part of every game as the kick-off. We must not drop it simply because the war is over. We should never forget what it stands for.” Only in 2009 did NFL players begin standing on the field for the national anthem before the start of primetime games. In 2016 the National Football League (NFL) stated that “players are encouraged but not required to stand during the playing of the National Anthem”.

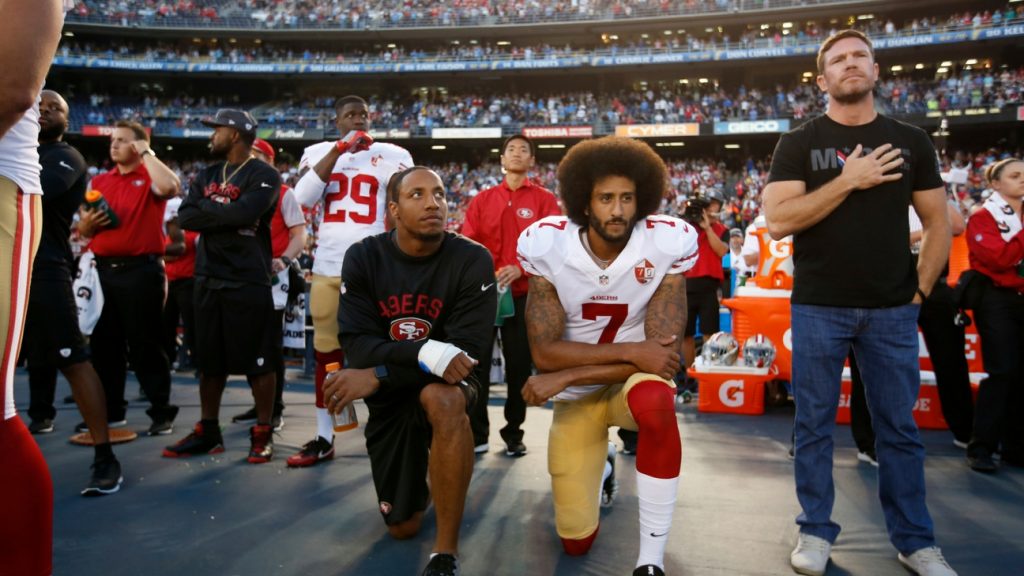

Approaching the San Francisco 49ers third preseason game of the 2016 season, a quarterback, recently recovered from three surgeries, and with a replacement just signed, was noticed sitting rather than standing during the national anthem. In a post-match interview, he explained, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.” He was referencing a series of deaths caused by law enforcement that led to the Black Lives Matter movement. In the 49ers’ final preseason game, having been advised by a teammate and U.S. military veteran, Nate Boyer, he took a knee during the national anthem to show respect rather than sit.

He later pledged to donate one million dollars to “Organisations working in oppressed communities.” Alongside his wife, he then founded the “Know Your Rights Camp”, an organisation which held free seminars to disadvantaged youths to teach them about self-empowerment, American history, and legal rights. The would-be President, Donald Trump, said, “He should find a country that works better for him.” The President later said he should have been suspended and listed his friendship with several NFL franchise owners.

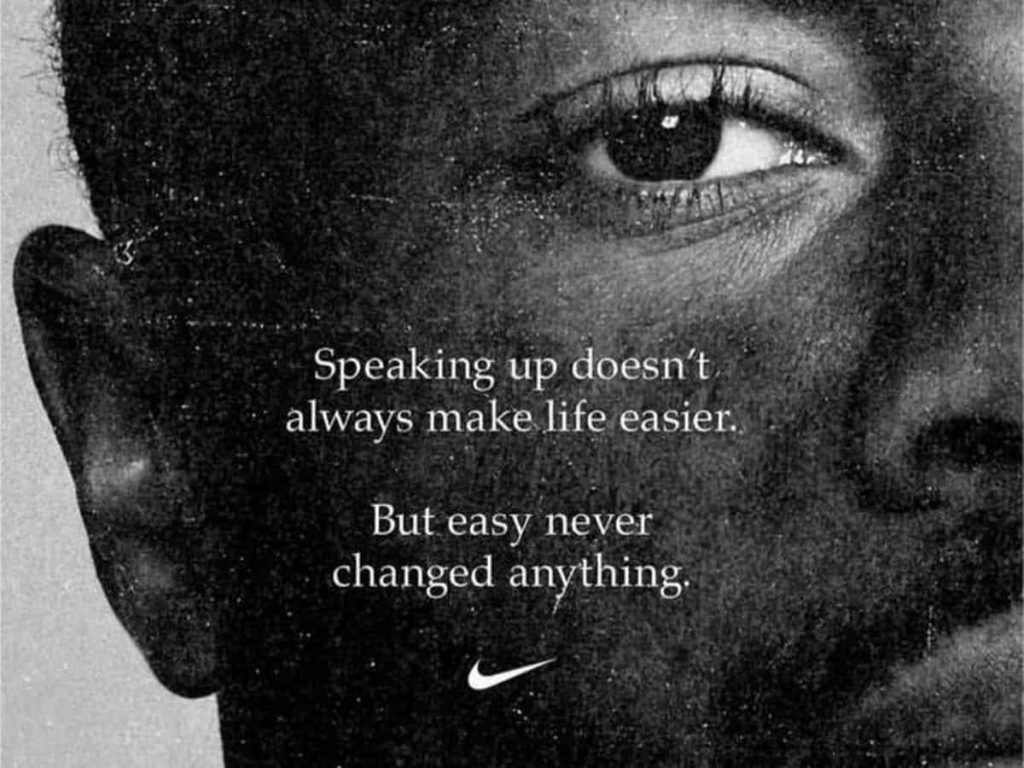

In 2017, the player was told he was being released from the San Francisco 49ers. On 3 March, he opted out of his contract and became a free agent. In 2018, Nike released an advertising campaign with the text, “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything.”

On 25 May 2020, George Floyd was killed by police during an arrest in Minneapolis. Events of his arrest, death, and the actions of the officers have led to international Black Lives Matter protests, calls for police reform, and legislation to address perceived racial inequalities. Four years before, the NFL player who took a knee in a preseason game said, “There is a lot that needs to change, one specifically is police brutality.” As of June 2020, Colin Kaepernick remains an unsigned quarterback formerly of the San Francisco 49ers, four years after taking a knee in a preseason match during the national anthem against perceived racial injustices.

This COVID-19 pandemic has impacted billions of people from celebrities and politicians to janitors and petrol attendants. There have been over seven million confirmed cases and 400,000 people have died. It is a truly global crisis. And during this crisis, or perhaps influenced by it, another pandemic has risen to the surface; one that has been bubbling for hundreds of years. It is a pandemic that is occasionally considered national news but still the current remains beneath the surface, sometimes being forcibly held under by the powers above.

Raheem Sterling, the Manchester City and England footballer, has been vocal in his support of Black Lives Matter, just as many other sporting superstars have been including Formula One driver Lewis Hamilton, boxer Anthony Joshua, gymnast Simone Biles, tennis players Naomi Osaka and Serena Williams and basketball players LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony and Michael Jordan.

In the words of Raheem Sterling, “This is the most important thing at this moment in time because this is something that has been happening for years and years. Just like the pandemic, we want to find a solution to stop it.” Or as Naomi Osaka said, “I hate when random people say athletes shouldn’t get involved with politics and just entertain. Firstly, this is a human rights issue. Secondly, what gives you more right to speak than me?” There are two global pandemics right now: both invisible, both dangerous and both need solving.

We haven’t had live sport attended by fans for months. Athletes have been training and preparing the best they can with uncertainty about what lies ahead. Events have been cancelled and the Olympics have been postponed. When so many other things are going on, it begs the question where sport fits into the dual pandemic narrative.

The reality is that sport matters, it has always mattered, possibly more now than ever. Sport and politics are historically so often interlinked even when it appears as though they aren’t or shouldn’t be. And sportsmen and women matter immensely as well. But not just for the reasons we might think but because their voice can cut through political bluster, misinformation, disinformation and fake news. Their voices and experiences are also a representation of society at large and their platform is one that can highlight uncomfortable issues that many ignore. For that reason, we need Colin Kaepernick, Raheem Sterling and LeBron James now just as we needed Tommie Smith, John Carlos and, of course, Jesse Owens, back then.